ECOLOGY ▪ EDUCATION ▪ ADVOCACY

An Indiana Native

Juglans: Combines the Latin Ju “ for Jupiter, king of the gods,” and glans meaning “nut.”

Cinerea: A Latin adjective meaning “ash-like,” or “ash-colored.”

joo-glans sin-ur-ee-uh

Lemon nut, oil nut, white walnut

Mature Size & Appearance: Medium-sized trees that usually grow to 12–18 m (40–60 ft) at maturity, but can occasionally reach heights as tall as 24–30 m (80–100 ft). The trunk diameter of mature trees is typically between 30–60 cm (1–2 ft), but occasionally as large as 1 m (3 ft) or more, and generally short in appearance before branching out into a broad crown, which varies in shape between flat and rounded.

Bark: Young trees have relatively smooth, light gray to light brown bark. As the tree ages, ash-gray colored crisscrossing furrows make shallow diamond-shaped designs with smooth, vertical ridges. The ash-colored bark provides the tree with its species name.

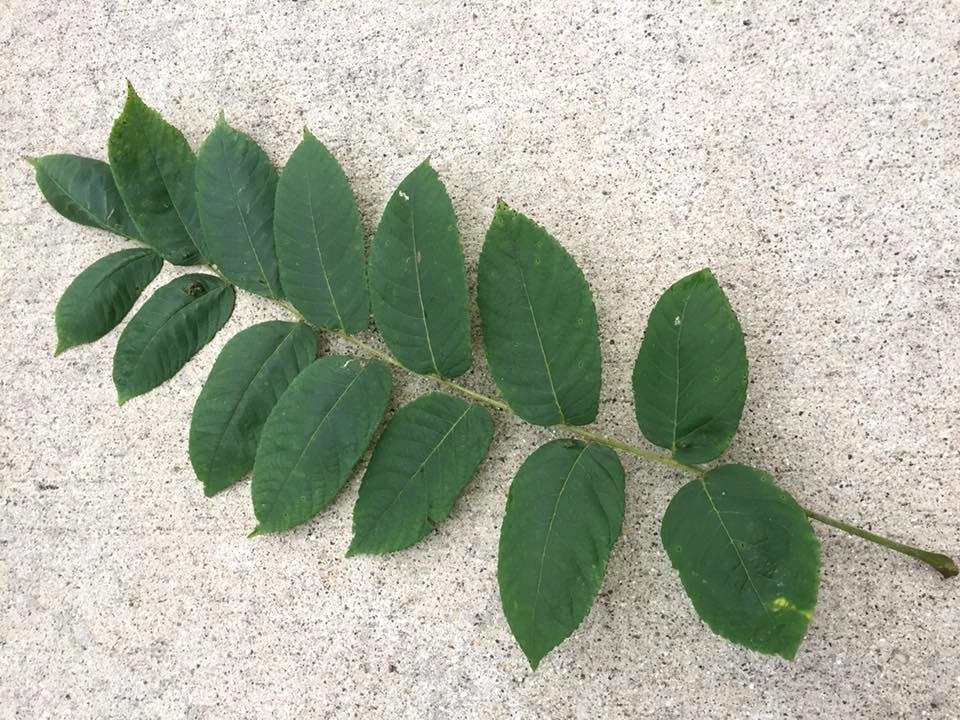

Leaves: Large Leaves, 27–76 cm (11–30 in) long, are alternate and pinnately compound with 11–17 finely-toothed, oblong to lanceolate-shaped leaflets each being 5–10 cm (2–4 in) long and approximately half as wide. Butternut leaves are usually oddly-pinnate and sessile except for the terminal leaflet. The yellowish-green leaflets are rough on the top, with soft hairs on the underside and are often sticky after they emerge. The leaves appear in May at the same time as the flowers.

Fall Color: Not showy; yellow-green leaves turn brown before dropping in early fall.

Twigs: Stout with chocolate-colored, thick-partitioned, chambered pith. Young twigs are green to orangish-brown, pubescent, and often sticky, becoming gray and smooth with age. Leaf scars are large, three-lobed, somewhat triangular, and often bordered by an elevated downy pad that resembles a mustache.

Buds: Terminal buds are 13–19 mm (.5–.75 in), downy, and with a blunt tip. Lateral buds are smaller.

Flowers: Unisexual, monoecious flowers appear with the leaves in late spring, usually May. The male flowers, located on drooping, greenish-yellow catkins, are approximately 5–12 cm (2–5 in) long. The smaller, bright red female flowers are erect and located on peduncles at the ends of the twigs. Flowers are wind-pollinated.

Fruit: Butternut fruits, which are technically called drupes and not nuts, mature in October in clusters of 1–5. The oblong, green fruit 5–7.5 cm (2–3 in) long, are covered with sticky hairs, and turn brown at maturity. The seed, contained within a hard shell called an endocarp, is 2.5–6 cm (1–2.5 in) long, deeply furrowed, and distinctly four-ribbed.

Life Expectancy: Butternuts are relatively short-lived trees with a lifespan of typically 75–90 years.

Key Characteristics: When identifying butternut, look for the following characteristics:

Similar Species: Butternut's closest Indiana relative is Black Walnut (Juglans nigra), which has bark that is darker and more deeply furrowed, lighter pith, fruit that is more round, and leaves that are typically evenly instead of oddly pinnate.

Hybrid: Introduced to the United States in the 19th Century, and colloquially known as “buartnut,” the hybrid Juglans x bixbyi is a cross between butternut (Juglans cinerea) and the Japanese walnut (Juglans ailantifolia). Butternuts are not said to hybridize with black walnuts (Farlee et al 2010).

Butternut trees were historically found statewide, but apparently, never in great abundance or large colonies. In Trees of Indiana, Charles C. Deam wrote that butternut is “a native of all parts of Indiana” (Deam 1921). However, in the 3rd revised edition, he added that butternut is “probably absent from Benton County” (Deam 1953).

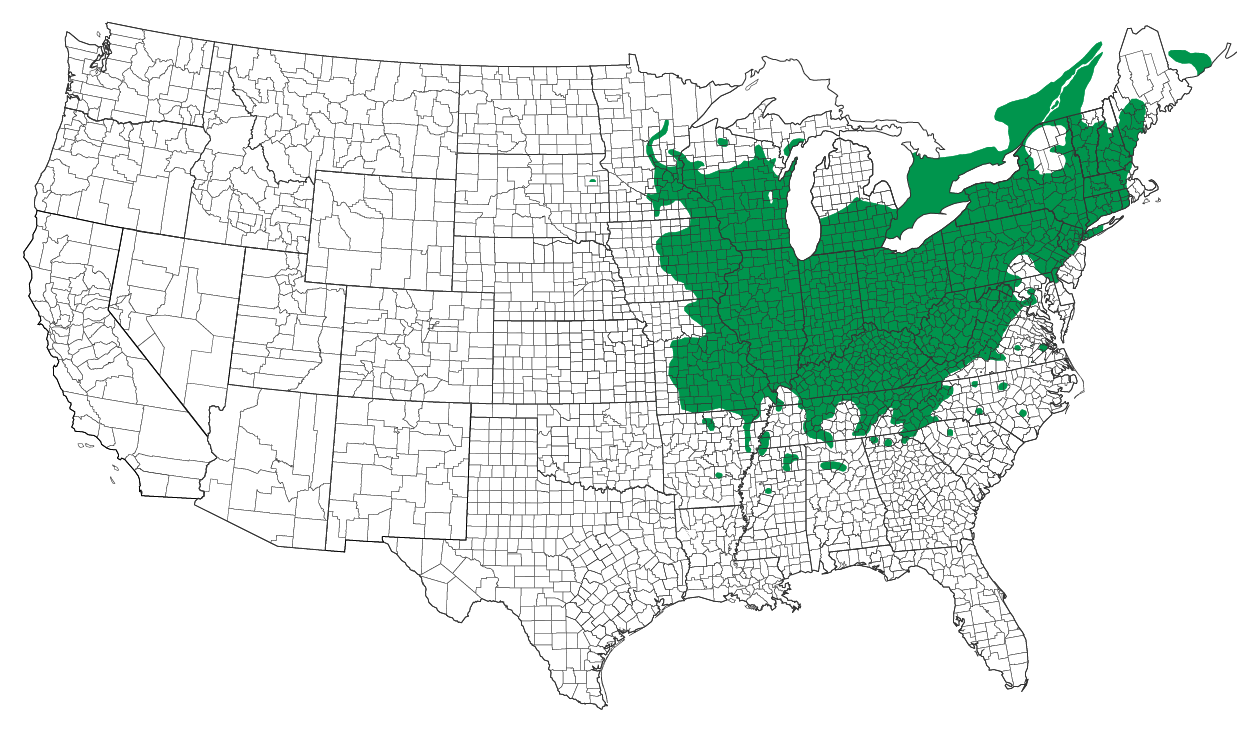

Juglans cinerea — Native Range

|

Species native to county, but may no longer persist. |

Butternuts prefer calcareous soils containing limestone and sometimes gravely substrates. Commonly found in sloped riparian areas, floodplains, and ravines, they often grow in soils that are fertile and moist, yet well-drained.

Butternuts are intolerant of shade and soil compaction, and the loss of suitable habitat and growing conditions is likely one of the factors in the decline of this species. As early as 1891, in their report entitled A Partial List of the Flora of Wabash and Cass Counties with Notes, geologist A.C. Benedict and geologist/physician M.N. Elrod M.D. wrote, “A few scrubby, half-dead butternuts, the last of their race, were seen. This tree seems unable to adapt itself to new conditions and is rapidly dying out. This is a pity, for it furnishes a beautiful wood for the cabinet maker and all excellent nut” (Benedict and Elrod 1891).

Culinary: American Indians consumed butternuts in a variety of ways, and the Iroquois' uses have been particularly well-documented (Sheu 2018). In addition to being eaten raw, the nuts were also crushed and mixed into other dishes and boiled to make baby food, pudding, and a drink (Moerman 1998). They also used oil derived from the nuts as a flavoring additive (Erichsen-Brown 1989), and syrup produced from boiled sap was used much like maple syrup (Sheu 2018).

When the first Europeans arrived in the New World, they also had a taste for butternuts, and a 20th-century finding is challenging some of the long-held theories regarding the exploration and discovery of the New World. A 1960s archeological excavation of L’Anse aux Meadowsas, the only known New World Viking settlement aside from Greenland, and dating back to 1000 A.D., turned up three preserved butternut husks. L’Anse aux Meadowsas, located in modern-day Newfoundland, is several hundred miles north of the native range of the butternut tree near what is now New Brunswick. Because of this, some historians now hypothesize that the Vikings may have traveled a good deal farther south than was previously believed (Wallace 2003).

Several centuries later, European settlers used butternut in much the same way as the Native Americans, and they also adapted them into new recipes, including as a flavoring additive in beer (Wood 2002).

Functional: Functionally: Native Americans used butternut trees for a variety of functional purposes. In addition to using butternut wood as a building material (Moerman 1998), several tribes constructed dugout canoes from butternut trunks (Tooker 1964). The young shoots, inner bark, and roots of butternut trees were boiled by Native American tribes to make dyes of varying colors from yellow, brown, and black (Sheu 2018). Some tribes created a hair conditioner by boiling the nuts into oil, and others mixed butternut oil with bear grease to create mosquito repellent (Moerman 1998).

European settlers used butternut wood for a variety of purposes but in different ways than it’s harder, darker cousin the black walnut (Juglans nigra). The golden-colored, close-grain wood, which takes well to polishing (Peattie 1948), was used for church altars, lecterns, interior trim, cabinetry, and as paneling in carriages and coaches, (Werther 1929; Hattermann 1984) but butternut’s most colorful role in American history occurred in the 1860s.

During the Civil War, Confederate soldiers, especially those hailing from areas where butternuts grew, wore uniforms dyed with the husks of butternuts. The durable, yet inexpensive dye colored the uniforms of the Confederate soldiers a yellowish-brown. The term “butternut” was used to describe these soldiers and was often used disparagingly as slang (Peattie 1948).

Medicinal: Native Americans had several known medicinal uses for butternut. Some tribes used the bark and sap as a cathartic used to expel worms, to cleanse diseased, wounded, or ailing parts of the body, and for bowel and urinary complications. The Potawatomi used a tea made from the inner bark to treat stomach ailments (MacPherson 1977), and the Iroquois used the bark to induce labor and to aid the side effects caused by menses (Moerman 1998). European settlers learned of the Native American practice of using the bark to treat toothaches, headaches, and as an all-around pain reliever, and butternut bark was stocked by many drug stores at least as late as the early 20th Century (Maxwell 1918).

Culinary: Butternuts are both highly nutritious and prized for their buttery taste. Consumed both raw and cooked, young nuts still in their green hulls may also be pickled (MacPherson 1977). Butternut sap, which has a high sugar content, can be boiled down to make a rich syrup. However, this practice is probably inadvisable due to the risk that creating a tapping wound could potentially provide an entry source for the deadly canker disease. Butternut nuts are still occasionally found locally in farmer’s markets and through some larger commercial suppliers.

Functional: Although scarcity and disease have impacted the commercial viability of butternut, butternut wood is still used by woodworkers for furniture, veneers, and cabinetry, and woodcarvers particularly favor the soft, rot-resistant wood for duck decoys (Wengert 2016).

Landscape: Butternut trees are very uncommon in Indiana landscapes. Sadly, the combination of susceptibility to disease, pickiness to site conditions, production of Juglone and lack of showiness/fall color has left them virtually excluded from the nursery and landscaping trades. Conservation-minded property owners should consider planting this historic but declining Indiana native tree.

As a member of the genus Juglans, and often called the "white walnut," the butternut shares some of the same rich folklore as its cousin, the black walnut.

The butternut tree was the inspiration for the following Indiana place names:

Elkhart County: Owned by Wilbur Peak, 118 Parker Ave., Elkhart, IN 46516 - Circumference 153 in, Height 78 ft, Crown 78 ft.

Note: during a brief walking survey in April 2019, the authors were unable to locate this tree at the listed address.

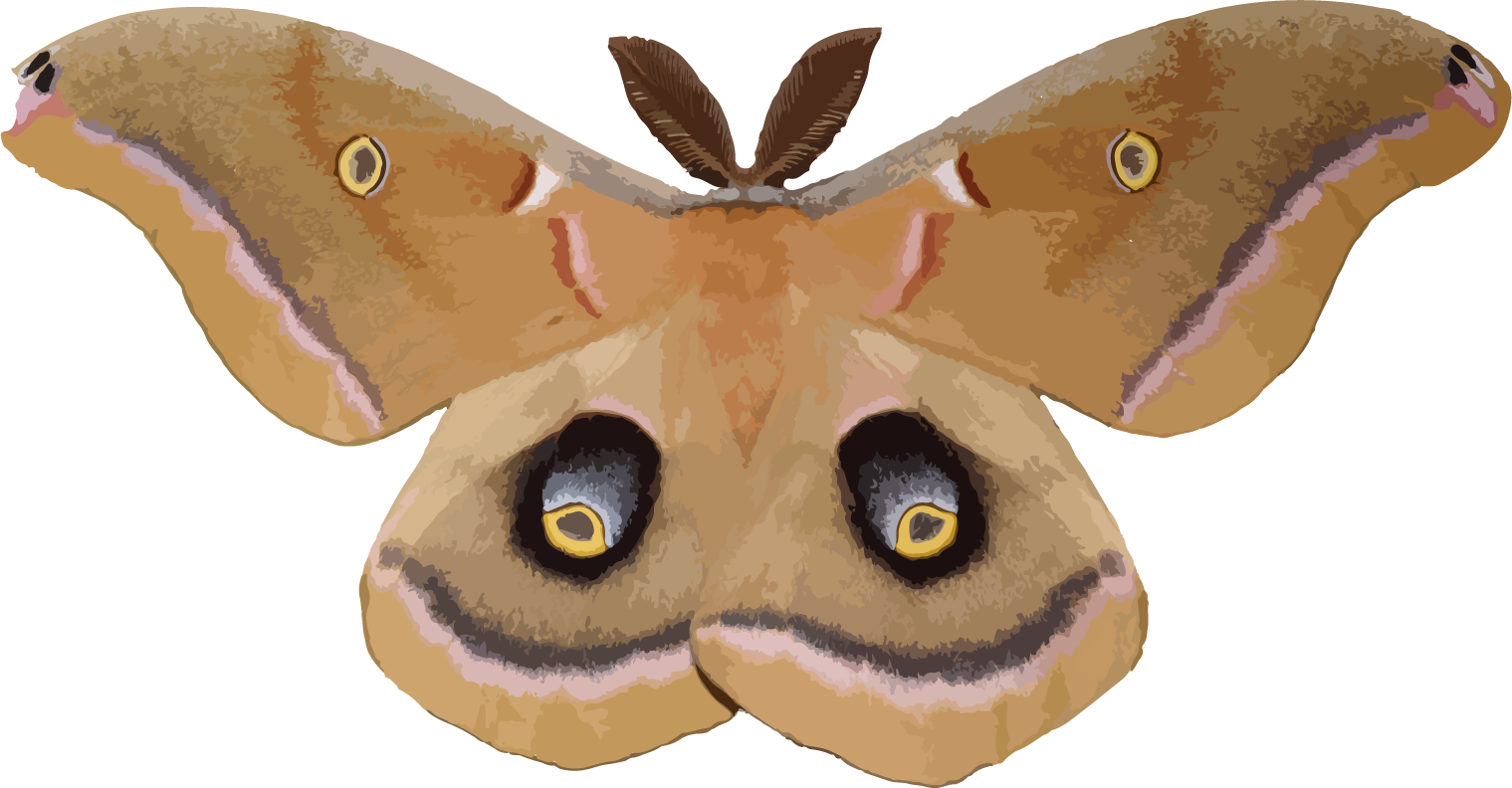

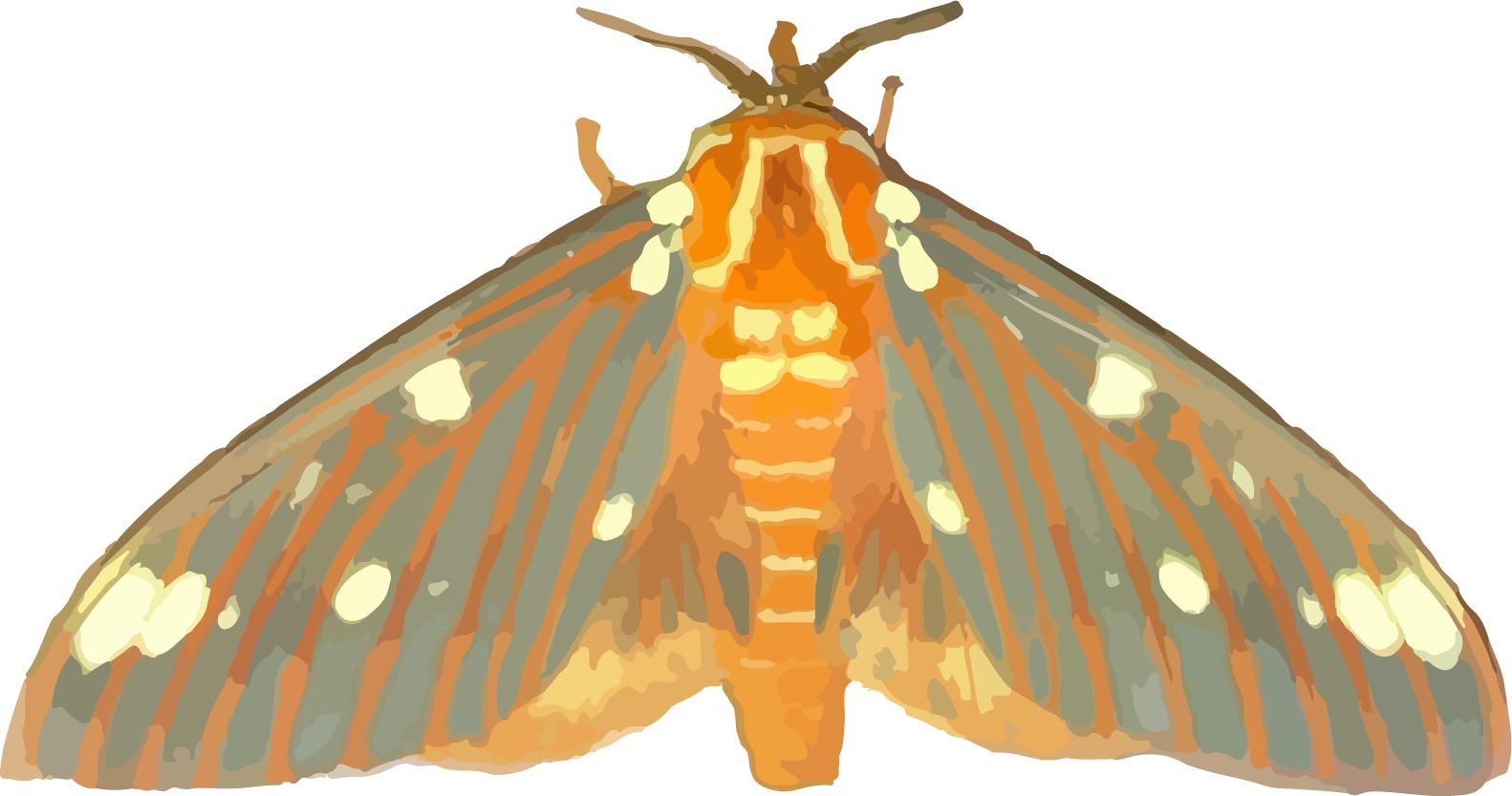

Butternut fruit is eaten by a large number of species when it is available. Eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), Allegheny woodrats, (Neotoma magister), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are known consumers of the nut. Several birds including red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus), black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), Carolina chickadee (Poecile carolinensis), tufted titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor), white-breasted nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis), red-breasted nuthatch (Sitta canadensis), Carolina wren (Thryothorus ludovicianus), yellow-rumped warbler (Setophaga coronata), pine warbler (Setophaga pinus), purple finch (Haemorhous purpureus), field sparrow (Spizella pusilla), and wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) been documented eating opened nuts (DeGraff 2002). Butternut trees provide a source of food for more than forty species of caterpillars.

The primary cause for the loss of an estimated 75+ percent of butternut trees nationwide is a fungal disease known as butternut canker (Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum). First observed in Wisconsin in 1967, and identified as a new species in 1979, the fungus, which is spread by wind, water, and insects, enters healthy trees through wounds and scars. Once infected, the fungus causes elliptical-shaped lesions with sunken centers that eventually join together to kill the infected tree, but not before the fungus produces spores that spread the disease to other trees.

Decades before the identification of the disease, Norman F. Smith, author of Michigan Trees Worth Knowing, wrote, “In addition, heavy winds and ice often break the brittle branches of this species providing entrance for fungi which cause the trees to rot inside at an early age, and often to die before reaching maturity” (Smith 1961).

Although there is currently no cure for the disease, the United States Department of Agriculture, Forestry Service, as part of an effort to reestablish Butternut populations in the Eastern United States, is propagating trees that have shown disease resistance (USFSR&D 2018).

Global Rank: G4 — apparently secure

Reasons: “Occurs infrequently in forest stands throughout most of the eastern United States and Canada. The abundance and condition are both in rapid decline due to butternut canker disease, with no known remedy. At the time of this review (2006), even with the canker evident and widespread, there are a large number of occurrences persisting and resistant trees, though rare, are found in many areas of the range. The species is not currently vulnerable to extinction, but there is certainly reason for longer-term concern. The rank should be reevaluated frequently” (NatureServe c2018).

National Rank: N3/N4 — vulnerable/apparently secure

Indiana State Rank: S3 — vulnerable

Indiana DNR Conservation Status: WL — watch list.

Propagation requires cold stratification. Collect fruit as soon as it falls, remove husks and place nuts in a plastic bag or another sealed container in the refrigerator for 3–4 months. Plant seeds in early spring in 1–2 inches of soil. Protection from squirrels will be necessary.

The requirement of an extended period of cold for seeds to break dormancy resulting in germination. Stratification is a process that occurs naturally though the colder period of winter, but it is often stimulated by horticulturists through refrigeration and other means.

In addition to the main GAINTP bibliography, the authors have used these additional sources:

Adams J. 2010. Butternut Hill: Restoring our Historic Homestead. [accessed 2018 Apr 27]. http://butternut-hill.blogspot.com/2010/08/welcome-to-butternut-hill.html.

Angier B. 1974. Field guide to edible wild plants. Harrisburg (PA): Stackpole Books.

Benedict AC, Elrod MN. 1891. A Partial List of the Flora of Wabash and Cass Counties with Notes. In Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources, Seventeenth Annual Report, pp. 260–272. Indianapolis (IN); William B. Burford; [accessed 2019 Apr 13]. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/9581/17_08%20A%20Partial%20List%20of%20the%20Flora%20of%20Wabash%20and%20Cass%20Counties%20with%20Notes.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

DeGraaf RM. 2002. Shrubs and vines for attracting birds. Lebanon (NH): University Press of New England.

Erichsen-Brown C. 1989. Medicinal and other uses of North American plants: a historical survey with special reference to the eastern Indian tribes. Mineola (NY): The Dover Press.

Farlee L, Woeste K, Ostry M, McKenna J, Weeks S. 2010. FNR-420-W Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids. West Lafayette (IN); Purdue University; [Accessed 2019 Apr 17]. https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/FNR/FNR-420-W.pdf.

Hattermann, DR. 1984. Juglans Cinerea: The American White Walnut. Eastern Illinois University The Keep Student Theses & Publications. [accessed 2019 April 16]. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=3791&context=theses

INDNR (Indiana Department of Natural Resources). 2016. Endangered, Rare, Threatened and Extirpated Plants of Indiana. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana Department of Natural Resources; [accessed 2018 Mar 24]. https://www.in.gov/dnr/naturepreserve/files/np-etrplants.pdf.

Leisso R, Hudelson B. 2008. Butternut Canker. Madison (WI): The University of Wisconsin; [accessed 2019 Mar 30]. https://hort.extension.wisc.edu.

Maxwell H. 1918. Indian medicines made from trees. American Forestry 24:206.

NatureServe Inc. c2018. Global Conservation Status Definitions. Nature Serve Explorer. Arlington (VA): NatureServe Inc; [accessed 2018 Mar 24]. http://explorer.natureserve.org/granks.htm.

Purdue Extension Forestry & Natural Resources. 2019. Endangered Trees of Indiana: Part II — Butternut (Juglans cinerea). West Lafayette (IN); [accessed 2019 Mar 30]. https://www.fs.fed.us/research/invasive-species/plant-pathogens/butternut-canker-disease.php.

Sheu, S. 2018. Butternut Butternut. Foods Indigenous to the Western Hemisphere. The American Indian Health and Diet Project. [accessed 2018 May 1]. http://www.aihd.ku.edu/foods/Butternut.html.

USFSR&D (United States Forest Service Research & Development). 2018. Butternut Canker Disease. [accessed 2019 Mar 30]. https://www.fs.fed.us/research/invasive-species/plant-pathogens/butternut-canker-disease.php.

Tooker E. 1964. An ethnography of the Huron Indians, 1615–1649. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 190. Washington (DC): U.S. Government Printing Office

Wallace B. 2003. The Norse in Newfoundland: L’Anse aux Meadows and Vinland. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies. [accessed 2019 Apr 16]; Vol 19, No1. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/nflds/article/view/140/236#no37

Wengert G. 2016. Butternut (White walnut). Madison (WI): Woodworking Network; [accessed 2019 April 19].https://www.woodworkingnetwork.com/knowledge-centers/wood-dr/butternut-white-walnut?fbclid=IwAR3ux1TMjVxQkNuSq3KYqi_bdwzxj6ODAZBJTJfaJdXvTWnsSite-SMLYiQ.

Werthner, BJ. 1935. Some American trees; an intimate study of native Ohio trees. New York (NY); Macmillan. p 84.

Wood Magazine Staff. 2018. Butternut: The Walnut’s Country Cousin. Boone (IA): WOOD Magazine; [accessed 2018 May 8]. https://www.woodmagazine.com/materials-guide/lumber/wood-species-1/butternut-historical-anecdote.