ECOLOGY ▪ EDUCATION ▪ ADVOCACY

Juglans: Combines the Latin Ju “ for Jupiter, king of the gods,” and glans meaning “nut.”

Nigra: Latin name for the word black.

JOO-glanz NY-gruh

American walnut, American black walnut, eastern black walnut

Mature Size & Appearance: Typically 18–27 m (60–90 ft) high, but occasionally 36 m (120 ft) or more. Trunks of mature trees are very large at 100–200 cm (3–6 ft) diameter and are often straight and unbranching for half of the height of the tree. Crown is usually open and wide-spreading.

Bark: Young trees gray to brown and scaley. Mature trees deeply furrowed with chocolate brown, intersecting inner bark.

Leaves: Large leaves 30–60 cm long (1–2 ft) are alternate and pinnately compound with 13–23 leaflets each being 5–10 cm (2–4 in) long and aromatic when crushed. Black walnut trees are one of the last native trees to leaf out in the spring and the flowers appear at the same time as the leaves.

Fall Color: Not showy. Leaves turn yellow then brown before dropping in early fall.

Twigs: Stout with tan-colored, thin–partitioned, chambered pith. Young twigs are cream-colored to orangish-brown, hairy, becoming gray and smooth with age. Leaf scars are large, three-lobed and heart-shaped with a conspicuous u-shaped notch in the top margin partially surrounding a lateral bud.

Buds: Terminal buds are 6–13 mm (.25–.5 in), hairy, and wide with a blunt tip. Lateral buds are smaller.

Flowers: Unisexual, monoecious flowers appear with the leaves in late spring, usually May. The male flowers are located on drooping, greenish-yellow catkins that are approximately 5–12 cm (2–5 in) long. Greenish, down-covered female flowers are located on peduncles at the ends of twigs. Flowers are wind-pollinated.

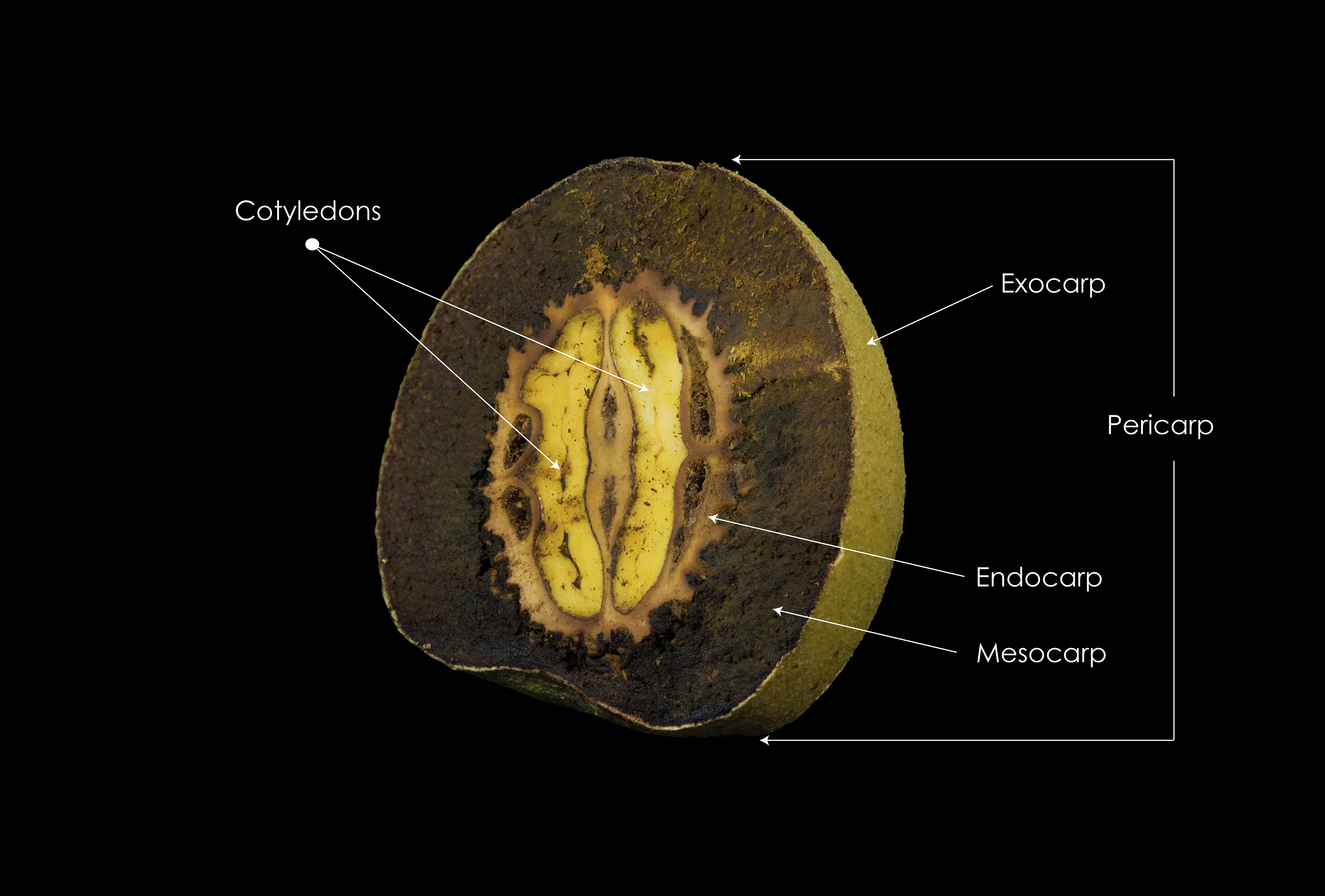

Fruit: Black walnut fruits, which are technically called drupes and not nuts, mature in early autumn in clusters 1–3. The round, green fruit, 4–5 cm (1.5–2 in) diameter, is aromatic, not sticky, and turns brown at maturity. The seed is contained within a hard shell, called an endocarp, which is typically 2.5–4.5 cm (1 –1.75 in) in diameter.

Life Expectancy: Black walnut trees are long-lived, reaching maturity in 150 years, but occasionally exceeding 200 years.

Key Characteristics: When identifying black walnut, look for the following characteristics:

Similar Species: The closest Indiana relative is the butternut (Juglans cinerea), which due to disease and habitat loss, is far less frequently encountered. Butternut differs from black walnut in usually having darker-colored pith, lighter bark, more oblong fruit, and leaves that are typically oddly pinnate. Young black walnut trees are most often confused with several species of Sumac (Rhus sp.) as well as with the invasive Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima). Refer to the leaf photos on this page for comparison. Only black walnut has all of the characteristics listed in the preceding paragraph.

Hybrid: The hybrid Juglans x intermedia, a cross between black walnut (Juglans nigra) and the English walnut (Juglans regia) is believed to first been described in 19th century France when French botanist Élie-Abel Carrière collected what he thought were Juglans regia seeds. Upon further study, the saplings that grew from the seed proved to be cross between the native European species and the imported North American walnut (Trees 1876). Known by several common names including Hind’s black walnut, intermediate walnut, and northern California walnut, the hybrid x intermedia has been cultivated for commercial purposes and has since naturalized in areas of Europe as well as in the United States (Kartesz 2014).

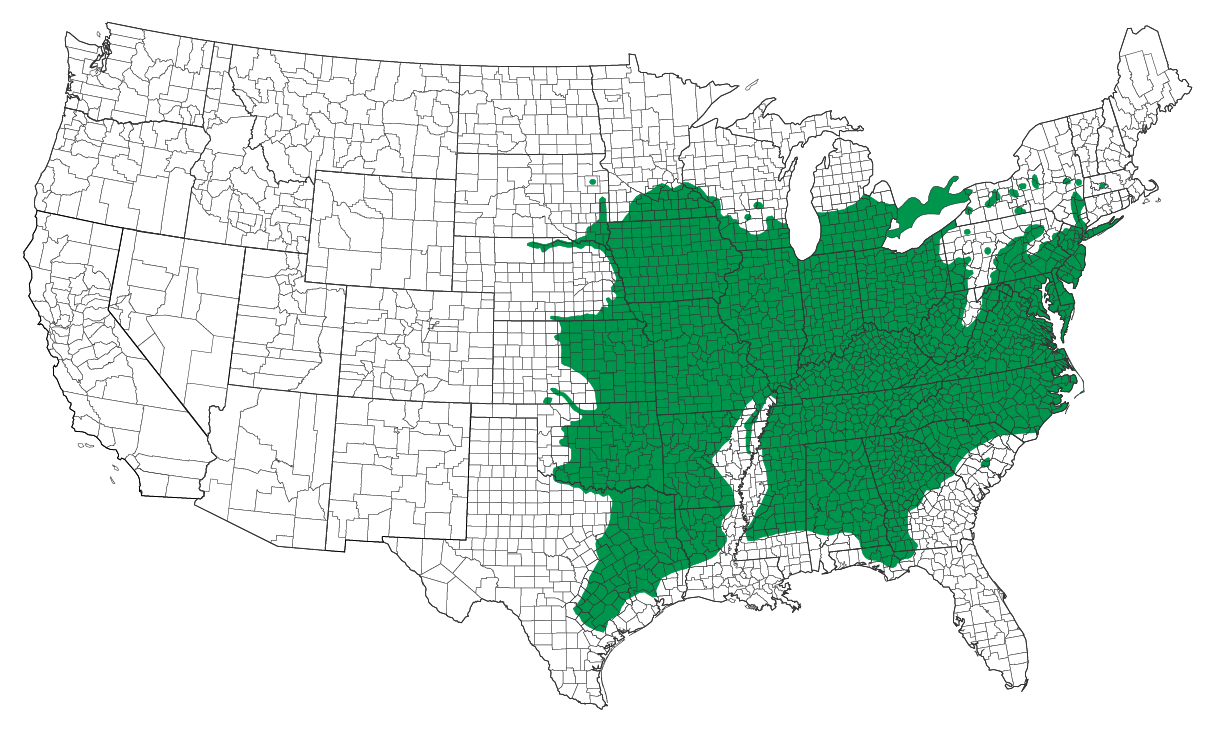

Native to the eastern deciduous forests of the United States, the native range of black walnut trees extends from the eastern seaboard to the central plains and from Texas through the middle of lower peninsula of Michigan, southern Ontario, and into portions of New England.

In Indiana, black walnut trees are found statewide. Charles C. Deam, in 1940, wrote in Flora of Indiana, “This species is probably a native of every county of the state. It is infrequent but well distributed in all parts of the state where it will grow” (Deam 1940). The Biota of North America Project (BONAP) depicts black walnut as being absent from 12 counties (Kartesz 2014), but one of their sources is Deam’s Flora of Indiana, which, along with Marion T. Jackson’s 101 Trees of Indiana, show Juglans nigra as being present in all of Indiana’s 92 counties (Jackson 2004). As a result of these sources, the following map illustrates black walnut’s range to include every county of the state.

Due to their timber and culinary value, the ecology and range of black walnut trees have been significantly altered. Outside of their native range, black walnuts have been planted extensively. Believed to have been introduced to England in 1629 (Nicolescu 1998), researchers have now documented naturalized populations of black walnuts in areas of central Europe (EUFORGEN 2017). In the New World, they were planted in the western states as well as Hawaii, and they are now documented to have naturalized in at least nine of those states (Kartesz 2014). Meanwhile, in their native range, as a result of changes in land usage and high demand for the lumber, naturally occurring trees are said to have declined significantly (Barkley and Brusven 2007).

Juglans nigra — Native Range

Juglans nigra — Indiana Range

|

Species native and present in county |

Opinions seem to differ regarding black walnut’s ability to tolerate a wide variety of soil and growing conditions. In Flora of Indiana, Charles C. Deam wrote, “It will grow almost anywhere and is a native in all kinds of soils except on the hills and in the flats of the southern part and on the sand hills of the northern part ” (Deam 1940). However, the authors of Michigan Trees: A Guide to the Tree of Michigan and the Great Lake Region wrote that black walnut “does not tolerate very dry, acid or wet sites” and “attains best development on warm, deep, fertile, moist, well-drained alluvial soils” (Barnes and Wagner 1981). Experts do seem to agree that black walnut is intolerant of shade, not a part of the climax forest community, typically found growing alone or in small stands, and that fire suppression has altered its place in the ecosystem.

Culinary: Like its Old World cousin English walnut (Juglans regia, the walnut found in supermarkets), black walnut has been a food staple for thousands of years. Native Americans consumed them both raw and cooked into a variety of dishes such as soups, porridges, bread, and cakes. The pungent flavor of crushed nuts and oil was used as a flavoring additive, and the Iroquois were said to have made a beverage from boiled, pressed nuts (Moerman 1998).

Functional: Native Americans used the wood of the tree for many things including ceremonially for items such as talking sticks and flutes (O’Driscol 2016). Several tribes used the bark to make brown and black dyes. The Cherokee used the wood to make furniture and for decorative carvings, and the Delaware and Iroquois used parts of the leaves and nuts as an insecticide to ward off fleas and mosquitos (Moerman 1998).

European settlers prized walnut wood for its grain, rich color, shock absorbency, and durability. Exported to England in the early part of the 17th Century, black walnut was used for a variety of purposes including carriage hubs, coffins, cradles, fine furniture, ship parts, tools handles and later, as airplane propellers. Walnut has been prized by gun-makers for centuries and was the preferred wood for shoulder weapons used during the Civil War and World Wars I and II. Colonists also continued the native tradition of using the husks as a hair dye (Peattie 1948; Turner 2013).

Medicinal: In ancient times, both the Greeks and the Romans associated old-world walnuts with fertility, and both peoples ate them to increase chances of conception. The Greeks associated the nuts with the god, Zeus, whereas, the Romans associated them with the goddess Juno, the wife of Jupiter, who is often associated with fertility.

In the 1500s and 1600s when doctors and herbalists followed the Doctrine of Signatures (DOS) as a guide for medicinal plants, they used walnuts to aid, heal, and promote prostate health. The DOS also recognized the visual similarities of the walnut to the human brain. The wrinkled look of the dried husk and the nut was thought to be a sign that it could help when the mind became “wrinkled” and, more broadly, walnuts were used to treat “matters of the mind” (Ji 2012). Additionally, walnuts have been used effectively as antifungal, antibacterial, antiparasitic, and antiseptic agents, and they’ve been used to treat everything from ringworm, snakebites, ulcers, scurvy, constipation, and heart-related issues (Moerman 1998).

Culinary Black walnuts are still used for a variety of culinary purposes. The nuts are used in baked goods, soups, salads, ice cream, as an ingredient in breading for seafood, and made into pickles. Pressed walnuts produce an oil that is used in salad dressing, as a flavoring additive and as a substitute for butter and olive oil (Hammons c2019). Similarly to maple trees, black walnuts are occasionally tapped for sap, which is then boiled down into syrup.

Black walnuts are highly nutritious and are often referred to as a superfood. Pound for pound, black walnut nuts have 50% more protein than meat (McPherson 1977), are packed with monounsaturated fats, like omega-3, as well as vitamins, flavonoids, and antioxidants. More information about the modern culinary uses and nutritional value of black walnuts is located in the page Juglans nigra - Natural Uses and Creative Adaptations

Functional & Economically: Black walnut remains one of the most valuable woods in Indiana, and contemporary uses for it include cabinetry, veneers, piano casing, sewing machines, and various types of fine furniture. According to the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service, “black walnut is the most valuable individual tree in Indiana based solely on the dollar value of the wood produced,” (Roberts 2017) and according to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, “there are an estimated 31.5 million walnut trees in Indiana. Approximately 17.7 million board feet of black walnut is harvested annually with a value of $21.4 million. If all forest walnuts in Indiana were lost because of TCD (Thousand Cankers Disease), it would represent a $1.7 billion loss” (IDNR 2014). Additional uses, including how to make black walnut dye and ink is located in the page Juglans nigra—Natural Uses and Creative Adaptations

Medicinal: Modern science has validated the connection between the physical characteristics of black walnut with neurological and prostate health. Several studies, including one from 2017, have linked the consumption of walnuts to improved cognitive performance and neuroprotective benefits (Goji et al 2017). Likewise, a study published in 2012 showed that men who ate 75 grams of black walnuts a day for 12 weeks had increased sperm vitality, mobility, and function (Robbins et al 2012). Black walnut oil is still used herbally for other medicinally long-held historical uses including as an anti-inflammatory. (Kim et al 2017).

Landscape: Sadly and ironically, Indiana’s most economically important tree and one that is enormously important to wildlife isn’t used very much at all in the home landscape and probably isn’t used at all by the landscape trade. It’s one of the last trees to leaf out in the spring, one of the first to drop leaves in the fall, doesn’t have significant fall color, produces nuts that many people consider messy, and emits a chemical that inhibits growth in nearby vegetation. However, certain plants such as Serviceberries and black Raspberries are immune to juglone poisoning and therefore make good companion plants.

Throughout history, people have embellished walnuts with rich lore. Consistent with their belief that walnuts impact fertility, Ancient Greeks were said to carry them as an aphrodisiac or love charm. Instead of rice, Roman wedding guests reportedly tossed walnuts at newlywed couples as a means of promoting increased fertility.

New World walnut lore is equally colorful and even more extensive. Certain superstitions dictated that burning walnuts would bring bad luck and that a large crop of walnuts foretold of a cold winter ahead (Beyer 2016). Thought to attract lightning, in the Ozark Mountains, black walnut trees were not allowed to grow near homes. Dutch Americans however, took the opposite approach with the belief that having the trees near homes would save the homes from lightning (Beyer 2016). In some areas, the nut was carried to prevent headaches (Beyer 2016) and used to treat depression (Watts 2007), and practitioners of American Hoodoo used baths of water steeped with walnuts to help afflicted people fall out of love or “expel” another person (O’Driscol 2016). Substantial amounts of additional black walnut lore exist that is beyond the scope of this webpage, and interested readers are encouraged to review the sources listed in the bibliography below for further information.

The names of the following places in Indiana are presumed attributed to the black walnut tree:

Elkhart County: Owned by Michael and Pamela Smith, 12172 CR44 Millersburg IN 46543 — Circumference 565 cm (222.48 in), Height 26.8 m (88 ft), Crown 26.5 m (87 ft).

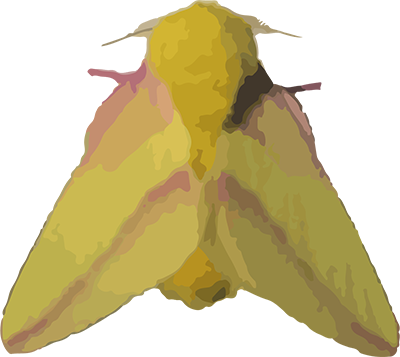

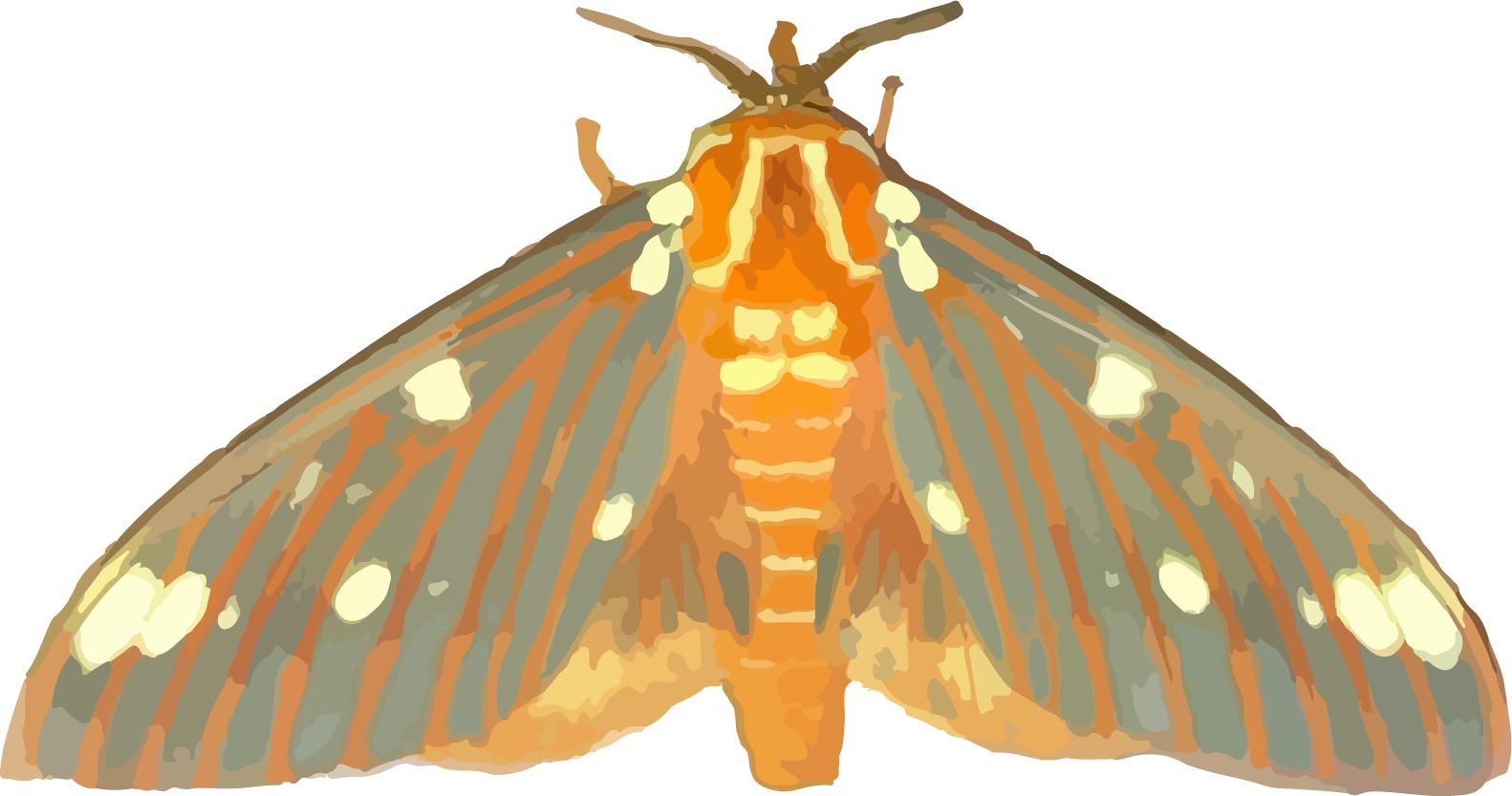

Black walnut fruit is an important food source for many mammals, particularly Fox Squirrels, and by one estimation black walnuts account for as much as 10% of their entire diet (Coladonato 1991). Several birds including Wild Turkey, Pileated Woodpecker, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Downy Woodpecker, Blue Jay, American Crow, Carolina Chickadee, Black-capped Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, Carolina Wren, Gray Catbird, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Pine Warbler, Baltimore Oriole, Northern Cardinal, Dark-eyed Junco, Field Sparrow, White-crowned Sparrow, and Song Sparrow have been documented eating opened nuts (Davison 1967 as cited by DeGraaf; Dugmore 1904; Martin et al 1951). Black walnut is a larval host plant for over 100 known species of butterflies and moths (see table to follow).

Thousand Cankers Disease (TCD) is a disease caused by a fungus (Geosmithia morbida) that is spread by the Walnut Twig Beetle (Pityophthorus juglandis); a beetle that is native to Arizona and New Mexico. The disease has been primarily attacking Juglans nigra planted in the western United States, which is out of its native range (TCD 2019). Western trees infected by the disease have a high mortality rate and typically die within two to three years of detection. (IDNR 2019)

In 2010, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources issued an emergency rule banning the transportation in Indiana of walnut products from nine western states and Tennessee (IDNR 2010). This rule (312 IAC 18-3-24) was finalized on May 22, 2013. In December of that year, the fungus

Word of the discovery of the Walnut Twig Beetle may have reached unscrupulous logging companies. In March 25, 2016 in an interview with the Greensburg Daily News, Marshall warned landowners to be on the lookout for logging companies attempting to convince them to sell their black walnuts now because of the threat of Thousand Cankers Disease (Spaulding 2016), which, at least at the time of this writing, does not appear to be threatening Indiana’s black walnut trees.

5: Secure

5: Secure  NR: Not ranked

NR: Not ranked

Black walnuts require cold stratification. Collect fruit as soon as it falls, remove husks and place nuts in a plastic bag or another sealed container in the refrigerator for 3–4 months. Plant seeds in early spring in 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in) of soil. Protection from squirrels will be necessary.

In addition to the main GAINTP bibliography, the authors have used these additional sources:

312 IAC 18-3-24. 2013. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana Natural Resources Commission.

Barkley YC, Brusven A. 2007. Black Walnut. Alternative Tree Crops Information Series #4. Moscow (ID): The University of Idaho; [accessed 2019 Apr 3].

Beyer, Rebecca. 2016. The Folkloric Uses of Wood: Part IV: Black Walnut. Blood and Spicebush. Barnardsville NC; [accessed 2017 Oct 17]. http://www.bloodandspicebush.com/blog/archives/02-2016.

Byrd, Chris. c2006-2013. Black Walnut Tree. Monroe (WA): Alderleaf Wilderness College; [accessed 2018 Feb 6]. https://www.wildernesscollege.com/black-walnut-tree.html.

Coladonato, Milo. 1991. Juglans nigra. In: Fire Effects Information System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory: Fort Collins (CO); [accessed 2019 Apr 10]. https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/jugnig/all.html.

Davison VE. 1967. Attracting birds: from the prairies to the Atlantic. New York (NY): Thomas Y Crowell Company.

DeGraaf RM. 2002. Shrubs and vines for attracting birds. Lebanon (NH): University Press of New England.

Dugmore AR. 1900. Bird homes. New York (NY): Doubleday & McClure.

EUFORGEN European Forest Genetic Resources Programme. 2017. Juglans nigra. Bonn (GR): European Forest Genetic Resources Programme; [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. http://www.euforgen.org/species/juglans-nigra/.

Gorji N, Moeini R, Memariani Z. 2018. Almond, hazelnut and walnut, three nuts for neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease: A neuropharmacological review of their bioactive constituents. Pharmacological Research Volume 129. Elsevier: Amsterdam (NE); [accessed 2019 Apr 9]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043661817311751?via%3Dihub.

Hammons Products Company. C2019. Wild Black Walnuts. Stockton (MO): Hammons Products Company; [accessed 2019 Apr 8]. https://black-walnuts.com/.

IDNR (Indiana Department of Natural Resourses). 2010. Emergency rule aimed at stopping tree disease. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana Department of Natural Resources; [accessed 2018 Feb 24]. http://www.in.gov/portal/news_events/57102.htm.

IDNR (Indiana Department of Natural Resourses). 2014. Thousand Cankers Disease detected in Indiana. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana Department of Natural Resources; [accessed 2019 Apr 6]. http://www.in.gov/activecalendar_dnr/EventList.aspx?view=EventDetails&eventidn=7133&information_id=14440&type=&syndicate=syndicate.

IDNR (Indiana Department of Natural Resource). 2015. Walnut Twig Beetle detected in Indiana. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana Department of Natural Resources; [accessed 2018 Feb 24]. http://www.in.gov/activecalendar_dnr/EventList.aspx?view=EventDetails&eventidn=7823&information_id=15952&type=&syndicate=syndicate.

IDNR (Indiana Department of Natural Resources). 2019. Thousand Cankers Disease. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana Department of Natural Resources; [accessed 2019 Apr 3]. https://www.in.gov/dnr/entomolo/6249.htm.

Ji, Sayer. 2012. Walnut and the ‘Doctrine of Signatures.’ Wake Up World; [accessed 2019 Apr 6]. https://wakeup-world.com/2012/02/10/walnut-and-the-doctrine-of-signatures/.

Kim Y, Keogh JB, Clifton PM. 2017. Benefits of Nut Consumption on Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Multiple Potential Mechanisms of Actions. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):1271. National Center for Biotechnology Information: Bethesda (MD); [accessed 2019 Apr 4]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5707743/.

Martin AC, Zim H, Nelson A. 1951. American Wildlife & Plants: A Guide to Wildlife food habits: the use of trees, shrubs, weeds, and herbs by birds and mammals of the United States. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill Book Company.

University of Minnesota Extension. Unknown. Growing black walnut. Unknown. University of Minnesota Extension: Minneapolis (MN); [accessed 2017 Oct 7]. http://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/yard-garden/trees-shrubs/growing-black-walnut/.

The Morton Arboretum. c2017. Plants Tolerant of Black Walnut Toxicity. The Morton Arboretum: Lisle (IL); [accessed 2017 Oct 4]. http://www.mortonarb.org/trees-plants/tree-and-plant-advice/horticulture-care/plants-tolerant-black-walnut-toxicity.

Murphy H. Unknown. Black Walnut. Foods Indigenous to the Western Hemisphere. AIHDP - The American Indian Health and Diet Project. [accessed 2019 Apr 2]. http://www.aihd.ku.edu/foods/black_walnut.html.

Nicolescu N. 1998. Considerations regarding black walnut (Juglans nigra) culture in the north-west of Romania. Forestry 71:349–354.

O’Driscol D. 2016. Sacred Tree Profile of Walnut (Juglans Nigra): Magical, Medicinal, and Edible Qualities. The Druid’s Garden. [accessed 2017 Oct 17]. https://druidgarden.wordpress.com/tag/juglans-nigra-lore/.

Peattie DC. 1948. A natural history of trees of eastern and central North America. Boston (MA): Houghton Mifflin Company. P. 121-125.

The Pennslyvania State University. Black Walnut. 2013. New Kensington (PA): The Pennsylvania State University; [accessed 2018 Feb 6]. http://www.psu.edu/dept/nkbiology/naturetrail/speciespages/blackwalnut.htm.

Robbins W, Xun L, FitzGerald L, Esguerra S, Henning S, Carpenter C. 2012. Walnuts Improve Semen Quality in Men Consuming a Western-Style Diet: Randomized Control Dietary Intervention Trial1. Biology of Reproduction 87. [accessed 2019 Apr 1]. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.112.101634.

Roberts S, Beineke W. Unknown. FNR-149: Important Information About Planting Black Walnut in Indiana. West Lafayette (IN): Purdue University Cooperative Exension Service; [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr/fnr-149.html.

Spaulding J. 2016. Indiana forest owners hold on to your black walnut trees. Greensburg (IN): Greensburg Daily News; [accessed 2017 Oct 19]. http://www.greensburgdailynews.com/opinion/columns/indiana-forest-owners-hold-on-to-your-black-walnut-trees/article_cdf4343e-739b-50f0-aa43-907cb576feaf.html.

TCD Thousand Cankers Disease. c2019. West Layayette (IN); [accessed 2019 Apr 3]. http://www.thousandcankers.com. Website is a collaborative effort between eight forestry entities.

Trees and shrubs: the walnut and its varieties. 1876. The Garden: An Illustrated Weekly Journal of Gardening in All Its Branches 9:361-363.

Turner MW. 2013. Remarkable plants of Texas: uncommon accounts of our common natives. Austin (TX): University of Texas Press.