ECOLOGY ▪ EDUCATION ▪ ADVOCACY

An Indiana Native

Acer: Latin word ǎcěr meaning “sharp,” which decribes the angled points of the leaves.

saccharum: From the Latin word succarum meaning “sugar,” which describes the high amounts of sugar in the tree’s sap.

ay-sur sak-ar-uhm

Black maple, hard maple, rock maple, rock tree, rough maple, sugartree, sugar tree, sweet maple

Mature Size & Appearance: Medium to large trees, typically reaching 18–30 m (60–100 ft), but occasionally to 36 m (120 ft); forest trees grow taller than specimen trees. The trunk diameter of mature trees ranges between 60–120 cm (2–4 ft). Open-growing trees typically have shorter trunks and broader, more rounded, symmetrical crowns than forest-grown trees.

Bark: The bark of young trees is smooth and light gray to light brown. As sugar maples mature, their bark becomes darker gray, furrowed, and broken into long, rough plates.

Leaves: Opposite, simple leaves are 7.5–15 cm (3–6 in) long and nearly equally as wide on slender, glabrous petioles 3.8–10 cm (1.5–4 in) long. The usually 5-lobed (sometimes 3-lobed), irregularly-toothed leaves have pointed tips and are dark green and glabrous above, lighter green and glabrous or nearly glabrous below.

Fall Color: One of the showiest maples with brilliant color and later onset than other maples; leaves turn vivid shades of yellows, oranges, and reds.

Twigs: Slender, smooth twigs are reddish-brown, glossy, and covered with pale, white lenticels. Leaf scars are rounded V-shaped.

Buds: Terminal buds are approximately 6 mm (.25 in) long, pointed, glabrous to slightly pubescent, and covered with numerous, reddish-brown scales. Lateral buds are smaller and pressed flat along the stems.

Flowers: Unisexual flowers appear with the leaves in April-May. Individual trees may be either dioecious or monoecious. Clusters of yellowish-green flowers dangle from hairy pedicels 2.5–7.3 cm (1–3 in) long. Both sexes of flowers are approximately 3mm (.25 in) long, have a 5-lobed, pilose calyx, and no corolla. Male flowers contain 7–8 stamens, and female flowers contain a single pistil with a hairy ovary. Flowers are wind-pollinated.

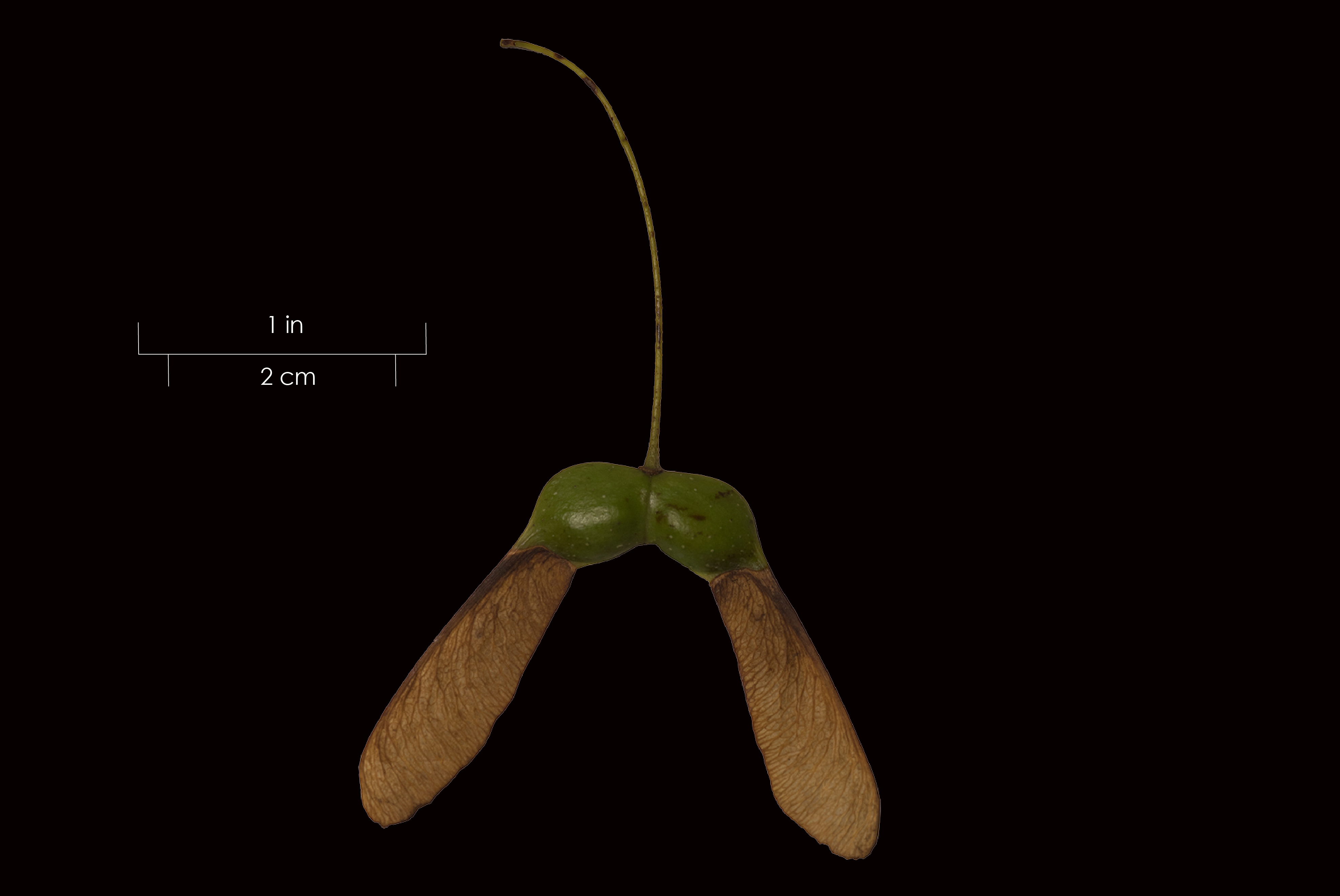

Fruit: As with all maples, sugar maple fruit consists of a single seed with an attached wing called a samara. The samaras are medium-sized , 2.5–3.8 cm (1–1.5 in) long, and hang in pairs nearly parallel to each other. Sugar maple samaras ripen and fall to the ground in September–October and germinate the following spring.

Life Expectancy: Sugar maple trees are long-lived. In optimum conditions, individuals may live up to 250–300 years. Growth is rapid for the first 35–40 years and slows afterward. Sugar maples attain maximum height at 125–150 years.

Key Characteristics: When identifying sugar maple, look for the following characteristics:

Similar Species: In Indiana, sugar maple (Acer saccharum) is one of five widespread maple trees with palmately-lobed, simple leaves. The closest genetic relative is black maple (Acer nigrum), which some taxonomists consider a subspecies of saccharum. Separating the two species can be challenging. Look for the following features in sugar maple: 5-lobed leaves that are relatively flat and glabrous, petioles that are glabrous and lack stipules, somewhat lighter-colored twigs.

The exotic Norway maple (Acer platanoides) also resembles sugar maple. Compared to sugar maple, Norway maple lacks the plated bark on mature trees, has flowers that are lighter green and physiologically dissimilar, and has leaves with rounded tips that excrete a milk-like sap when broken.

The taxonomic placement of sugar maple (Acer saccharum), black maple (A. nigrum) and their variations have been a contested taxonomic debate for many decades. The classifications represented on this page reflect the contemporary taxonomic placement by the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

Hybrids: Sugar maple is so closely related to black maple, that many taxonomists have considered A. nigrum to be a subspecies of A. saccharum. Recent genetic studies suggest that only geographical range and not morphology are useful for separating the two species (Skepner and Krane 1998). Where their ranges overlap, the two species form naturally occurring hybrids.

Subspecies, Varieties, and Forms: Botanists have described numerous variations, but currently, ITIS recognizes only two varieties:

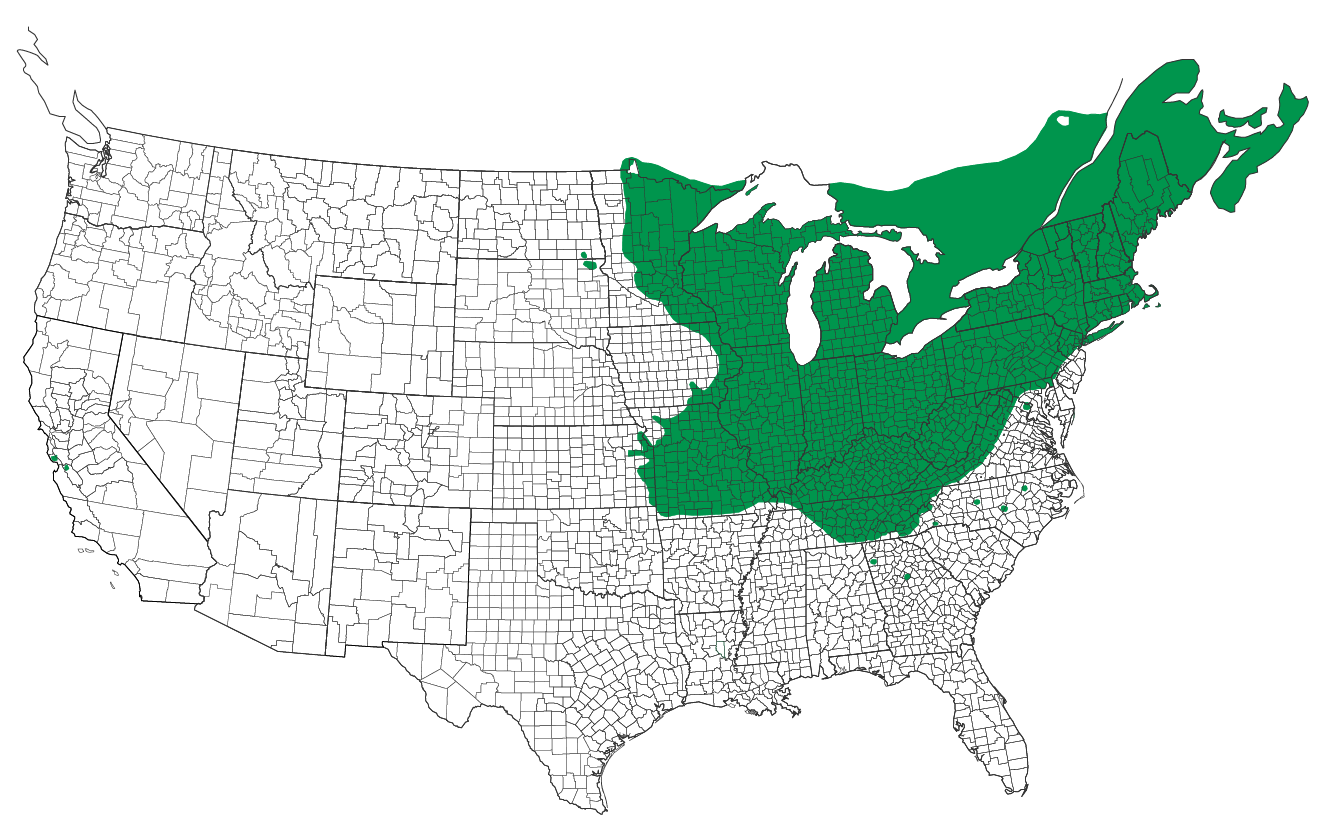

Sugar maples are native to most of the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada extending southward to portions of Tennessee and westward to Kansas. In Indiana, they are native and present in every county. In Trees of Indiana, Charles C. Deam wrote that sugar maple is “a frequent to common tree in all parts of Indiana. It is confined to rich uplands or along streams in well-drained alluvial soil. Throughout our area, it is usually associated with beech. It is absent in the ‘flats’ of the southeastern part of the state and on the crests of the rides of the ‘knob’ area of Indiana. It is a frequent or common tree on the lower slopes of the spurs of the ‹knobs.’” (Deam 1953)

Acer saccharum — Native Range

|

Species native and present in county |

Sugar maple trees thrive in deep, well-drained, mesic soils. Although they are somewhat tolerant of sandy and rocky soils, they are rarely, if ever found in wet, poorly-drained soils. Shade tolerant, sugar maples are one of the primary components of the climax beech/maple forest where their abundant leaves create deep shade and contribute to the richness and fertility of the soil.

Culinary: Perhaps no other North American tree has a more celebrated culinary history than sugar maple. Due to the high sugar content and the consistent late winter flow of its sap, the indigenous North American people developed many food products from sugar maple trees. Though there is some debate regarding whether pre-contact Native Americans had the ability or equipment to render sap to syrup or sugar, early documentation by Europeans indicates that historic Native Americans were well-practiced in various applications of the sugaring process.

Tribes including, the Algonquin, Cherokee, Dakota, Iroquois, Malecite, Menominee, Meskwaki, Micmac, Mohegan, Ojibwa, and Potawatomi all processed the sap into syrup or sugar. (Moerman 1998). The Iroquois mixed maple sap with thimbleberries and water into a fermented beverage. Ojibwa and Potawatomi enjoyed sugar maple sap directly from the tree but also allowed it to sour into a vinegar-like seasoning for cooking venison and other meats. The abovementioned tribes, as well as the Menominee and Meskwaki, used maple sugar as a seasoning for meat, much like salt is today. The Potawatomi made a taffy-like candy for the children by pouring the hot syrup onto the snow, and the Iroquois used the dried, processed bark as an ingredient used in bread and cake (Moerman 1998). The abundance of sugar maple trees in parts of North America and their absence in other parts made maple food products a valuable commodity for tribes such as the Chippewa in intertribal commerce.

American Abolitionists followed the writings of Dr. Benjamin Rush, Thomas Jefferson, Eastman Johnson, and William Cooper. These men and others called on people to make and purchase maple sugar to “lessen or destroy the consumption West Indian sugar, and thus indirectly to destroy negro slavery” (Stanton 1990). In a 1797 essay entilted Advantages of the Culture of the Sugar Maple Tree, Dr. Rush wrote, “Whoever considers that the gift of the sugar maple trees is from a benevolent Providence, that we have many millions of acres in our country covered with them, that the tree is improved by repeated tappings, and that the sugar is obtained by the frugal labor of a farmer’s family, and at the same time considers the labor of cultivating the sugar cane, the capitals sunk in sugar works, the first cost of slaves and cattle, the expenses of provisions for both of them, and in some in ... market, in all the West-India Islands, will not hesitate in believing that the maple sugar may be manufactured much cheaper, and sold at a less price than that which is made in the West-Indies” (Rush 1791).

Functional: Native Americans used the hard, straight-grained wood of sugar maple in a variety of ways. The Chippewa and Ojibwa fashioned it into cooking tools, including spoons and bowls. The Micmac made bows and arrows from the wood, the Cherokee used it for carving, and the Malecite made torch handles from sugar maple wood (Moerman 1998).

European settlers to New England also prized sugar maple wood, and they used it for a variety of purposes, including furniture, cabinetry, and hardwood flooring (Peattie 1948).

Medicinal: At least three Native American tribes developed medicinal uses from parts of the sugar maple tree. The Iriquois were the most notable as they created compounds and decoctions to treat smallpox, eye and vision ailments, shortness of breath, and as a blood purifier. The Mohegan and Potawatomi tribes developed cough remedies and expectorants from the inner bark (Moerman 1998).

Culinary: With the highest sugar content of any maple tree, sugar maples continue to be an economically important food crop throughout the northeastern United States. Although in 1900, Indiana ranked third in the nation for maple syrup production (McPherson and McPherson 2007), the state is no longer in the top 10. However, maple sugaring continues to be a popular late-winter tradition when the nights are cold and the days are warm when visitors by the thousands visit parks throughout Indiana to learn about the time-honored sugaring process.

Other parts of the sugar maple tree also have culinary uses. The seeds are said to be tasty when eaten raw, steamed, roasted, and ground into flour (McCarthy 2015). The inner bark can be ground into a paste and used as a thickening agent (PFAF 2019) and used to make bread (Yanovsky 1936).

Functional: Furniture makers use the hard, light-colored, close-grained solid wood and veneer of sugar maple for cabinets and furniture. Strong and shock-resistant, it is ideally suited for dance and gymnasium floors, baseball bats, billiard cues, and bowling alley lanes and pins. Along with black maple (Acer nigrum), Sugar maple (Acer saccharum) is branded and sold as “hard maple, and the two are indistinguishable by the lumber trade.”

Due to its desirable tonal properties, sugar maple wood is also extensively used in the production of musical instruments. In addition to piano soundboards, luthiers use it in the construction of various types of stringed instruments, including acoustic guitars, electric guitar necks, violins, and cellos.

Abnormalities causing distinctive, striking grain patterning known as birds-eye, curly, and tiger maple are particularly valuable to furniture and instrument makers alike.

Medicinal: The authors have found no additional contemporary medical uses for sugar maple.

Landscape: Their hard wood, long life, dense canopy, and relative disease resistance make sugar maples ideal shade trees for rural and suburban landscapes and parks. However, given their broad crown, relative intolerance of pollution, salt, and drought, sugar maples are not ideal urban street trees.

The nursery trade has developed numerous cultivars, including some that are drought tolerant and have an upright form. Some notable ones are as follows:

Native American cultures have numerous stories related to the sugar maple, and many of the tribes’ tales revolve around the work involved with reducing the sap to sugar and the seasonality of sugaring.

Other stories describe how the Native Americans discovered the sweetness of the sap of sugar maples.

The foliage of sugar maple, particularly when wilted, is considered toxic to horses and unsuitable for browsing (Dunkel 2019).

Sugar maple was either the direct or indirect inspiration for the following Indiana names:

Johnson County: Owned by Charlene Legan, 1370 North 400 West Bargersville, IN 46106 — Circumference 254.9 in, Height 84 ft, Crown 75.05 ft.

In Indiana, sugar maple is a source of food to most of the same fauna as other native maples, 10 birds, 11 mammals, including at least 108 species of native moths, and various additional insects. Cavities in mature trees are utilized as nesting locations by Black-capped Chickadees, Eastern Screech Owls, Pileated Woodpeckers, Northern Flickers, and other cavity-nesting birds (Hilty 2020).

| Known Mammal and Bird Associates in Indiana | ||

| Taxonomic Name | Common Name | Parts used |

|---|---|---|

| Class Aves (Birds) | ||

| Bonasa umbellus | Ruffed Grouse | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Coccothraustes vespertinus | Evening Grosbeak | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Colinus virginianus | Northern Bobwhite | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Haemorhous purpureus | Purple Finch | seeds, buds and flowers |

| Meleagris gallopavo | Wild Turkey | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Pheucticus ludovicianus | Rose-breasted Grosbeak | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Sitta canadensis | Red-breasted Nuthatch | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Sphyrapicus varius | Yellow-bellied Sapsucker | sap |

| Spinus tristis | American Goldfinch | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Zonotrichia albicollis | White-throated Sparrow | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Class Mammalia (Mammals) | ||

| Castor canadensis | American beaver | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Glaucomys volans | southern flying squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Microtus pennsylvanicus | meadow vole | seeds |

| Odocoileus virginianus | white-tailed deer | twigs and foliage |

| Peromyscus leucopus | white-footed mouse | seeds |

| Procyon lotor | North American raccoon | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus carolinensis | eastern gray squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus niger | fox squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus vulgaris | red squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sylvilagus floridanus | eastern cottontail rabbit | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Tamias striatus | eastern chipmunk | seeds |

| Ursus americanus | black bear (extirpated) | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

Foliage Diseases

Stem Diseases

Vascular Diseases

Trunk rots

Damaging Insects

In addition to the primary bibliography, the authors have referenced the following sources:

Dunkel B. 2019. Acer - an overview. Sciencedirect.com. [accessed 2020 Feb 16].

[GMMSRC] The Green Mountain Maple Sugar Refining Company, Inc. 2020. History of Maple. Vermontpuremaplesyrup.com. [accessed 2020 Mar 21]. https://vermontpuremaplesyrup.com/history-of-maple/

McCarthy M. 2015. Maple’s Other Delicacy. Northern Woodlands. [accessed 2019 Dec 20]. https://northernwoodlands.org/outside_story/article/maples-other-delicacy

Santamour F, Jacot McArdle A. 1982. Checklist of cultivated maples. II. Acer saccharinum Marshall. Journal of Arboriculture 8.

Skepner A, Krane D. 1998. RAPD reveals genetic similarity of Acer saccharum and Acer nigrum. Heredity 80, 422–428. [accessed 2020 Feb 15]. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00312.x

Stanton L. 1990. Sharing the dreams of Benjamin Rush. Charlottesville, (VA): Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation.

Rush B. 1791. An account of the sugar maple-tree, of the United States, and of the methods of obtaining sugar from it, together with observations upon the advantages both public and private of this sugar. Ann Arbor (MI): Text Creation Partnership. [accessed 2020 Mar 21]. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N19030.0001.001/1:2?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

Yanovsky E. 1936. Food plants of the North American Indians. Washington: United States Department of Agriculture.