ECOLOGY ▪ EDUCATION ▪ ADVOCACY

An Indiana Native

Acer: Latin name for “maple tree.”

Saccharinum: Combines the Greek word sakkharon, meaning “sugar,” with the Latin adjectival suffix inum for “of or like” to form “of sugar.”

ay-sur sak-kar-eye-nuhm

Creek maple, large maple, river maple, silverleaf maple, soft maple, swamp maple, water maple, white maple.

Mature Size & Appearance: Large trees at maturity, typically between 18–24 m (60–80 ft) high but occasionally 30 m (100 ft) or more, forming a broad, rounded to elm-shaped crown. Trunk diameter can reach 60–120 cm (2–4 ft) at maturity, but it often divides near the ground into multiple sub-trunks of similar sizes.

Bark: The bark of young trees is light-gray to brownish and smooth becoming darker gray to reddish-brown with maturity with loose, shallowly-grooved plates that are often shaggy and peeling away from the trunk.

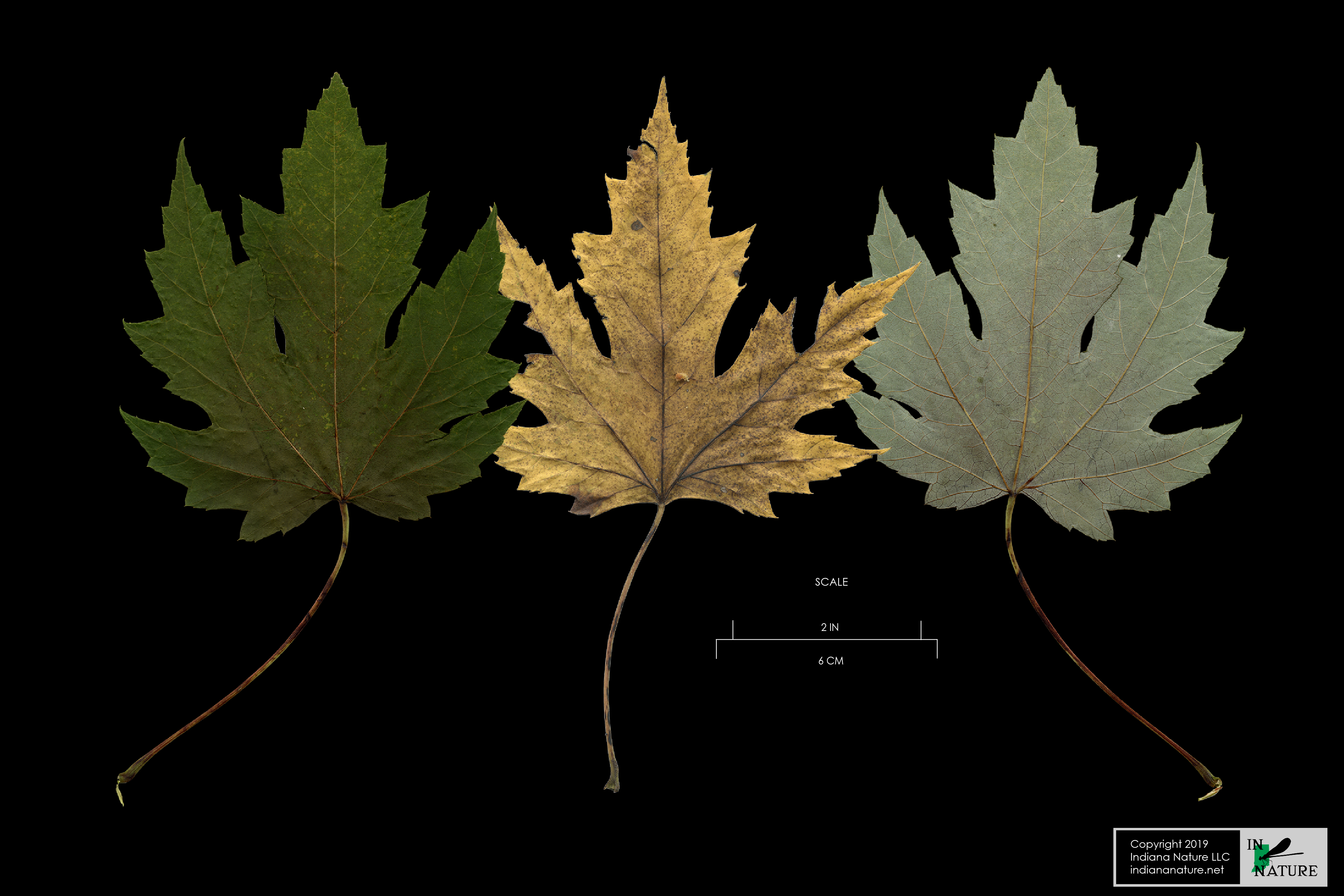

Leaves: Opposite, simple leaves are typically 18–25 cm (7–10 in) long with blades approximately 10–15 cm (4–6 in) in length and nearly as wide with petioles 7.5–10 cm (3–4 in). The drooping, five-lobed leaves are sharply-toothed and deeply cut towards the midrib. The upper surfaces of the leaves are pale green, the lower surfaces silvery-white, and the base of the leaf blade ranges from truncate to heart-shaped.

Fall Color: Not showy; Leaves turn grayish-green to pale yellow.

Twigs: Twigs are slender and smooth with pink pith. Young twigs are green turning reddish-brown with age, and emit a foul odor when broken. Twigs often curve upwards towards the tips.

Buds: Buds are approximately 5–6 mm (.19–.25 in) long and covered with 3–4 pairs of dark red, smooth, lustrous scales. Leaf buds are opposite on the twigs and are often accompanied by somewhat larger and rounder flower buds, which also occur in clusters on short stalks, particularly away from the ends of twigs.

Flowers: Unisexual flowers appear before leaves in March–April. Individual trees may be either dioecious or monoecious and may change from year to year. Flower clusters grow laterally along the twigs or on short shoots of the prior year’s growth in densely-crowded, sessile umbels. Each flower cluster consists of 3–6 flowers, which are typically, but not always, the same gender. Each flower contains a 5-lobed calyx and no corolla. Male flowers contain 3–7 greenish-yellow stamens, while female flowers have a single hairy pistil with two, bright-red styles. Flowers are primarily wind-pollinated.

Fruit: As with all maples, silver maple fruit consists of a single seed with an attached wing called a samara. Silver maple samaras, the largest of all Indiana native maples, at 3.8–7.6 cm (1.5–3 in) in length, hang in pairs that are joined at the base, together forming an angle of about 90-degrees. The samaras germinate shortly after dropping to the ground, usually in May.

Life Expectancy: Silver maple trees begin producing seed at 11 years or later (Burns and Honkala 1990), reach maturity at approximately 90 years of age, and typically live to be no older than 125–140 years. Growth is rapid for the first 25–30 years and slows afterward.

Key Characteristics: When identifying silver maple, look for the following characteristics:

Similar Species: In Indiana, silver maple (Acer saccharinum) is one of five widespread maple trees with palmately-lobed, simple leaves. Red maple (A. rubrum) is the most visually and genetically similar. Red and silver maples occur in similar habitats, both are known commercially as “soft maples,” and the two occasionally hybridize. Distinguishing silver maple from red and other maples can be done by utilizing the key characteristics above.

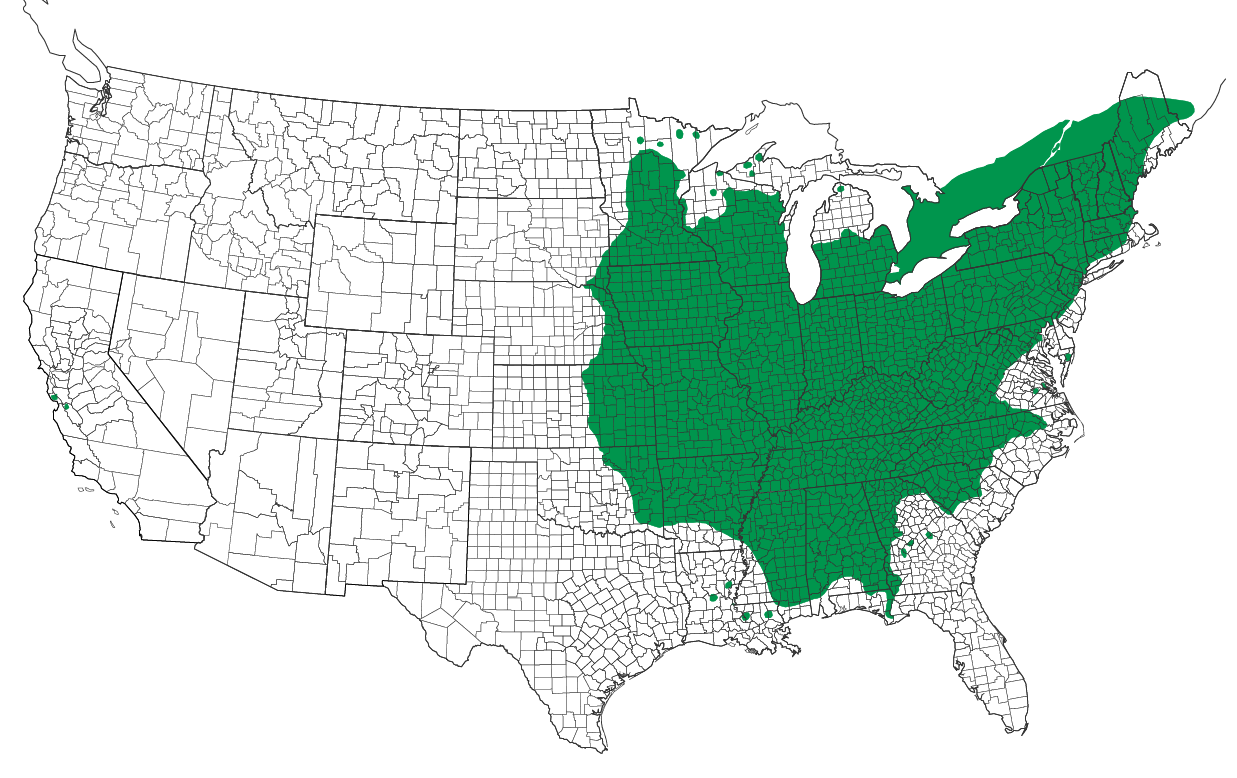

Silver maples are likely native to every county in Indiana. In Trees of Indiana, Charles C. Deam wrote that silver maple is “locally frequent to very common in all parts of Indiana” (Deam 1953), and Marion T. Jackson wrote in 101 Trees of Indiana that they are found “throughout Indiana” (Jackson 2004).

Acer saccharinum — Native Range

|

Species native and present in county |

Silver maple is historically a lowland species of rich wetlands including, the edges of small lakes, ponds, and streams along with the bottomlands of creeks and other areas where frequent flooding occurs. However, tolerance of a variety of conditions has led to widespread ornamental planting throughout the state.

Culinary: Although silver maple has a lower sugar content than other maples (Conger 2019), Native Americans and early settlers boiled the sap into sugar and syrup, respectively. The Chippewa, Dakota, Iroquois, Ojibwa, Omaha, Ponca, and Winnebago tribes all used sugar produced from silver maple trees as a sweetener (Moerman 1998). The Iroquois’ use of silver maple also included using the sap mixed with thimbleberries and water and then fermenting it into alcohol, and using the dried, processed bark as an ingredient of breads and cakes (Moerman 1998). Early settlers, specifically in the Ohio River Valley, found silver maple syrup to be of better quality than that of sugar maple. However, it’s rate of flow was much slower than sugar maple, which made it less commercially marketable (Peattie 1948).

Functional: Native American tribes had several known uses for silver maple. The Chippewa boiled the bark of silver maple with the bark of other trees to make a substance that they used to remove rust. The Cherokee carved the relatively soft wood into decorations, and the Ojibwa used the wood in arrows and the roots as bowls in a game called “pugasaing,” a dice-like game played by children and adults (Moerman 1998).

Medicinal: Native Americans developed various medicinal uses for silver maples. The Cherokee used a bark infusion as a pain relief for cramps, for the treatment of diarrhea due to dysentery, and for treating menstruation-related issues. The Ojibwa also used the bark for treating intestinal ailments but also as a diuretic, and they used the bark of the roots for treating gonorrhea. As a dermatological aide, silver maple was used by the Cherokee to treat hives and measles, and a concoction made from boiled bark was used by the Chippewa to clean sores. The Mohegan people treated coughs with an infusion of bark, collected explicitly from the south face side of the tree, and Iroquois used an alcoholic beverage made from fermented silver maple sap, thimbleberries, and water as a painkiller (Moerman 1998).

Culinary: Although not considered to be commercially significant, silver maple trees are frequently tapped for sap and made into syrup. According to one study, the seeds, comprised primarily of protein, starch, and sucrose, have a “high food value” (Anderson 1918), and are tasty when eaten raw, steamed, roasted, and ground into flour (McCarthy 2015). The inner bark can be ground into a paste and used as a thickening agent (PFAF 2019) and used to make bread (Yanovsky 1936).

Functional & Economically: Along with red maple (Acer rubrum), silver maple is sold commercially as “soft maple.” Although less desirable than the so-called “hard maples” of sugar maple (A. saccharum) and black maple (A. nigrum), the wood of silver maple is still economically valuable. Various uses for silver maple wood include furniture, veneer, fuel, flooring, crates/pallets, paper, interior trim, woodenware, musical instruments, turned objects, wagons, and tool handles. Occasionally, the sapwood of silver maple contains highly coveted, naturally occurring visual aberrations known by woodworkers as quilting or curling.

Medicinal: The authors have found no additional contemporary medical uses for silver maple.

Landscape: Due to their attractiveness, fast growth, and tolerance of salt, drought, and air pollution, silver maples were once popular midwestern street trees. They have since fallen from favor with urban foresters as their soft-wooded limbs are frequent victims of storms and high winds, and their shallow roots often cause damage to sidewalks and sewer lines. As such, many municipalities no longer plant silver maples as street trees, and some forbid residents from doing the same.

However, that is not to say that silver maples have no place in the contemporary landscape. Given the proper setting, located away from power lines, sidewalks, sewer lines, and buildings, silver maple trees retain the attributes that made them once-popular street trees.

Plant breeders have developed many cultivars of silver maple. Some of them are as follows:

Most folklore related to maples focuses on the genus as a whole. However, one specific belief is exclusive to silver maple trees. As the wind associated with the leading edge of a storm would blow against the trees, the silvery undersides of the leaves become apparent. Seeing the silvery undersides was believed to signify that an oncoming storm was imminent.

The foliage of silver maple, particularly when wilted, is considered toxic to horses and unsuitable for browsing (Dunkel 2019).

The only known Indiana place names for the silver maple tree are streets located in Carmel, Greenwood, Kewanna, Indianapolis, St. John, and Zionsville.

Union County: Owned by Dian Paquet, 5475 North Patterson Road, Liberty, IN 47353 - Circumference 269.4 in, Height 96 ft, Crown 104 ft. (see photos on this page)

In Indiana, silver maple is a source of food to most of the same fauna as other members of the maple (Acer) genus, including at least 58 species of native moths, 10 birds, 11 mammals, and various additional insects. Silver maple buds are said to be a particularly important food source for squirrels as their emergence comes at a time when winter food supplies are exhausted. (Reichard 1976 as cited by Burns & Honkala 1990)

| Known Mammal and Bird Associates in Indiana | ||

| Taxonomic Name | Common Name | Parts used |

|---|---|---|

| Class Aves (Birds) | ||

| Bonasa umbellus | Ruffed Grouse | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Coccothraustes vespertinus | Evening Grosbeak | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Colinus virginianus | Northern Bobwhite | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Haemorhous purpureus | Purple Finch | seeds, buds and flowers |

| Meleagris gallopavo | Wild Turkey | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Pheucticus ludovicianus | Rose-breasted Grosbeak | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Sitta canadensis | Red-breasted Nuthatch | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Sphyrapicus varius | Yellow-bellied Sapsucker | sap |

| Spinus tristis | American Goldfinch | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Zonotrichia albicollis | White-throated Sparrow | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Class Mammalia (Mammals) | ||

| Castor canadensis | American beaver | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Glaucomys volans | southern flying squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Microtus pennsylvanicus | meadow vole | seeds |

| Odocoileus virginianus | white-tailed deer | twigs and foliage |

| Peromyscus leucopus | white-footed mouse | seeds |

| Procyon lotor | North American raccoon | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus carolinensis | eastern gray squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus niger | fox squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus vulgaris | red squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sylvilagus floridanus | eastern cottontail rabbit | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Tamias striatus | eastern chipmunk | seeds |

| Ursus americanus | black bear (extirpated) | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

Silver maple (Acer saccharinum) is subject to many of the same diseases that are common to other maples (Acer spp.) including:

Silver maple seeds require no stratification, and they will germinate immediately upon falling to the ground. Seeds saved for storage should be collected when their moisture content is at 30% or more, and they should be stored at that level to maintain viability. Propagation is said to have the best success when seeds are grown in moist, mineral-rich soil (Burns and Honkala 1990). Silver maples may also be propagated vegetatively through softwood or hardwood cuttings or by layering.

In addition to the primary bibliography, the authors have referenced the following sources:

Acer saccharinum. 2019. Treesandshrubsonline.org. [accessed 2019 Dec 28]. https://treesandshrubsonline.org/articles/acer/acer-saccharinum/.

Arkham T, Jabbour A. 2014. Black Cats and White Wedding Dresses. Broomall: Mason Crest.

Anderson R. 1918. A note on the analysis and composition of the seed of the silver maple. Geneva: New York Agricultural Experiment Station.

Conger A. 2019. A Comparative Analysis of Sugar Concentrations in Various Maple Species on the St. Johns Campus. [accessed 2019 Jun 20]. https://employees.csbsju.edu/ssaupe/CV/conger_final_report.pdf

Dunkel B. 2019. Acer - an overview. Sciencedirect.com. [accessed 2019 Dec 28]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/acer

Gilman D, Watson E. 1993. Acer saccharinum. Forest Service United States Department of Agriculture.

Guy, N. (n.d.). Plant guide: silver maple. [Accessed 17 Dec. 2019]. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/pg_acsa2.pdf

Laurence H. 2015. Cultivars of Woody Plants: Genus Acer excluding A. palmatum. Laurence Hatch Press.

McCarthy M. 2015. Maple’s Other Delicacy. Northern Woodlands. [accessed 2019 Dec 20]. https://northernwoodlands.org/outside_story/article/maples-other-delicacy

Reed S, Bayly W, Sellon D. 2018. Equine internal medicine. W.B Saunders Company.

Reichard, TA. 1976. Spring food habits and feeding behavior of fox squirrels and red squirrels. American Midland Naturalist 96:443-450.

Santamour F, Jacot McArdle A. 1982. Checklist of cultivated maples. IV. Acer saccharinum L. Journal of Arboriculture 8.

Sullivan, Janet. 1994. Acer saccharinum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). [Accessed 28 Dec. 2019]. https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/acesah/all.html

Yanovsky E. 1936. Food plants of the North American Indians. Washington: United States Department of Agriculture.